Sports are a drug.

They’ve probably always been a drug, and always will be a drug.

They soothe us, distract us, energize us, unite us, divide us, and entertain us.

They also blind us.

Americans are sports junkies.

And what do addicts do?

Deny that a problem or addiction exists in the first place. They ignore the obvious. They defend the indefensible. They keep right on using.

But they’ll ruin you. Mess up your mind.

You don’t believe me, do you?

So how about the fact that sports will make you deify someone you’ve never met? Doubt me?

Let me prove it to you.

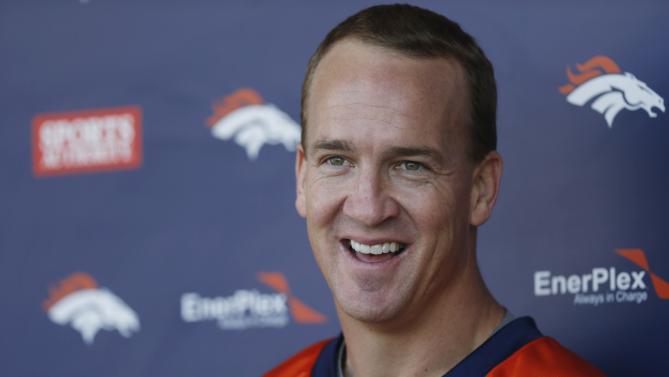

How do you feel about Tom Brady? And now, how do you feel about Peyton Manning?

Allow yourself to independently judge both of these legends’ and their recent “situations.”

You couldn’t do it, could you?

Manning’s stories are promptly dismissed as “hit” jobs by people who want to tear him down through accusations of HGH and a young college kid who behaved immaturely.

Yet Brady’s stories are treated as fact, despite the little evidence produced in the 12 months since Deflategate began to actually prove 1) anything actually happened and 2) most importantly as it concerns Brady himself, that he had anything to do with it if the balls were actually deflated by humans.

The NFL still slings it out in court to prove they have the right to punish a player under the CBA, missing the entire point that, you know, you have to actually have proved the player should be punished at all. To do this, they uncovered thousands of e-mails and phone records to try and link Brady to it.

All we found out is he wants to play longer than Manning, he’s got an ego and he weirdly cares a lot about swim pool covers.

On the other side of the coin, Manning has seen his image take a hit over allegations that date back 20 years that he was basically a pervert to a female trainer at the University of Tennessee. This is on top of the allegations that he received several shipments of HGH (or his wife did) that coincide with his neck injury rehabilitation a few years back.

The Tennessee story has been out there since 1996 and Manning has settled the dispute twice – once when it happened and apparently again when he brought the trainer’s name up in a book. Why this is resurfacing now has everything to do with his name being attached to a Title IX lawsuit against Tennessee and it being 2016, the age of rabid, social media heathenry.

Meanwhile, it has been revealed that NFL players were shorted $100 million in revenues. The league office dismissed it as an accounting error. Anybody make a $100 million mistake at their job wouldn’t have a job the next day. Yet this story is not currently gaining much traction. Why?

Because we’ve already given them the money, so we don’t care if the rich players get richer or the rich owners are even richer. It’s monopoly money to us, anyway.

No, no, we addicts, we care about sentiment, about legacy, about being able to emphatically agree on some fantasy ranking of the greatest ever.

And we care about this all because it says a lot about who we are – at least so we think subconsciously. We attach ourselves to these athletes and these teams so we can go through the pain of losing and the joy of winning together. Brady backers love the underdog story, Manning’s fans stuck by him through all the “he can’t win the big one” years. To us, this loyalty proves something about us.

We can’t like the wrong guy, we can’t be wrong, we can’t have invested in the wrong guy or bought into who he is as a person.

There’s a lot on the line for us average Jill and Joe’s because we’ve convinced ourselves that our fandom matters to other fans. We made it clear who we support – and not only is our guy better, but they are a better person, too.

Except for one, small problem.

It means nothing. We don’t know any of these people. We don’t know what they are like behind closed doors. We don’t know how kind they are or how ruthless they are or how sleezy they might be.

They might be innocent, they might be guilty. The vast majority of us have no clue. And yet we sports junkies feed the beast. We listen to the sports talk shows rattle on and on about it, driving up ratings, making them talk about it more. We click the stories all over social media, prompting more stories to be written about it.

We’re sheep. Inmates in a sports asylum walking around with blinders on, believing in sports and sports figures as if it was a religion. We’re dopes, buying the gear, buying the tickets at astronomical prices, buying into the belief systems and serious manner in which it’s all treated.

We’ve been sucked into world within our world where we think this stuff actually matters, like debating if four minutes is enough of a suspension for Ben Simmons cutting class last week?

I don’t know, and I don’t care anymore. Did that teach Simmons anything? Probably not. Why is he allowed to do that? Why do you care? Didn’t you cut class in college? Does it impact you if he doesn’t go to class?

We want fairness and equality in sports, in college programs? There’s too much money at stake to ever let it happen. We demand from coaches and athletes and administrators that which we ourselves cannot even do in our daily lives. We take shortcuts. We skip out. We complain. We don’t give max effort every single day.

But we sure expect everyone else in sports to. After all, they’ve been given a gift.

So have you.

You just choose to waste it.

Sports and extracurricular activities in general serve in building people in a variety of ways from a young age. They teach teamwork, dedication, commitment, perseverance and hard work to name just a few.

And wanting to be a part of that, as a parent or a fan, or both is good too. But too much of anything can turn into something you never intended – like convincing yourself that someone you’ve never met is good or evil, the embodiment of everything you love about sports – or everything you loathe.

Just be wary of absolutes.

Absolutes lead down a path of yelling at officials at a soccer game for four-year-olds. They make you crazy enough to attack someone physically in the parking lot after a game. Or throw batteries at Santa Claus (we’re looking at you, Philadelphia).

They make you believe in someone else that, like you, is human and fallible. Better yet, these absolutes have led you to wear the jersey of a character, a portrayal, an image of who that person wants you to see and believe.

I know this isn’t easy to admit. I know you think I’m crazy, that sports don’t control your life and that you couldn’t possible “worship” another human being so blindly.

But just go back to the beginning. What do you know and believe about Tom Brady? And what do you know and believe about Peyton Manning. Ask yourself which one is right and wrong, good and evil, guilty or innocent.

And now remember that it’s a trick question: you don’t know them or their situations – only what their enemies or their mouthpieces have allowed you to.

In other words, you don’t know Peyton Manning or Tom Brady. Or Michael Jordan. Or Tiger Woods. Or Bob Knight. Or Serena Williams. Or Dean Smith. Or Kobe Bryant. Or Tim Duncan. Or LeBron James. Or Andre Aggasi. Or Danica Patrick.

No matter how much you think you do.

The first step is to admit there’s a problem.

Sports are a drug.

They soothe us, distract us, energize us, unite us, divide us, and entertain us.

And they most certainly blind us.

If it seems like the NFL is in a dark place right now, it is because it does seem that way. But seeming to be is not the same as it actually happening. To be fair, the NFL, NBA and the world in general are not any darker or different than it was 25 or 30 years ago.

If it seems like the NFL is in a dark place right now, it is because it does seem that way. But seeming to be is not the same as it actually happening. To be fair, the NFL, NBA and the world in general are not any darker or different than it was 25 or 30 years ago.