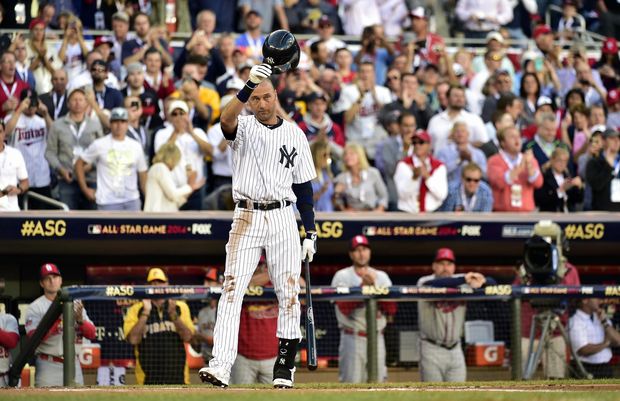

For an examination of all that ails our decaying American culture and society, look no further than Derek Jeter’s first at-bat in the 2014 Major League Baseball All-Star Game.

Jeter got the unbelievably kind gesture of a couple fastballs, right down the middle. These courtesy pitches, from Adam Wainwright, were meant allow the great Jeter a chance to get a hit in his final All-Star game before retiring at season’s end.

Never mind that this game is supposed to be important because it decides home-field advantage for the World Series.

Never mind that this game is supposed to be important because it decides home-field advantage for the World Series.

“I was going to give him a couple pipe shots,” St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Adam Wainwright said. “He deserved it.”

Frankly, aside from the free pass to be publicly idolized, Jeter didn’t deserve to be there based simply on merit. He ranks as one of the worst shortstops in the majors this season. But the fans determine who goes to the All-Star game, and they wanted their hero in the game.

But while America paid #re2pect to Derek Jeter, I #cringed.

The Nike ad that went viral this week on Jeter was touching, very cool and well done, but this embarrassing display of over-honoring our sports heroes serves as yet another reminder that we have got societal shortcomings that must be addressed.

For starters, there is the humility of Derek Jeter during the 2014 Fare Thee Well tour. For example, to put that ad together, Nike needed Jeter’s cooperation. They needed him to film it.

Can it be a touching, poignant tribute if you played a part in filming scenes for it? Can you be humble and do the “awe, shucks, you shouldn’t have” routine if you are participating in the shine? Following the All-Star game, after being named MVP, Jeter spoke at the press conference about how a night about him wasn’t a night about him.

The paradoxes are endless here. But this is not Derek Jeter’s fault.

No, his hubris aside, these grandiose gestures are bypassing the unspoken rules we have been ignoring for a long time, anyway. We decided to bid a long farewell before they actually are gone, all to appreciate what they have given us.

What they’ve given us is something to latch on to and distract ourselves from. That’s all sports are – entertainment. They can teach us about heart, effort, teamwork and dedication, but more often than not, they serve as a distraction from the day-to-day simplicity of life.

Jeter and the Yankees are the best representative of this. There was something about the mid-to-late 1990s. New York seemed to be on resurgence in cool. Part Seinfeld and Friends, part Yankees, part Rudy Guiliani. And we looked to the Yankees following 9/11, looked to follow their lead with American pride literally bursting with emotion.

Maybe that’s why we’re so wrapped up in honoring these guys, even though our gratitude has been paid (literally – and in millions) for years.

We are attached to our professional athletes, dangerously so. We ask far too much of them to support our emotional imbalance from our own lives feeling unfulfilled.

It can engulf us, our families, our friends, and in the case of Cleveland, an entire region.

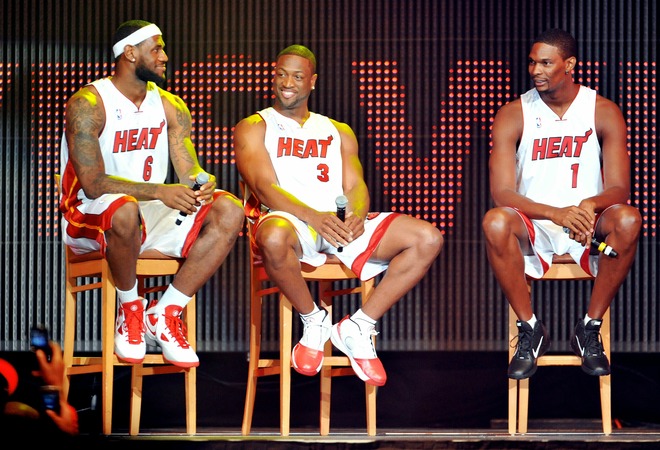

We were so quick to jump on the fairy tale bandwagon of LeBron James return to Cleveland and the Cavs, that we overlooked everything prior to it. The unbiased media was biased in rooting for LeBron’s return home.

They ignored all the prior theories about why and how he left the Cavs in the first place to gush about a love story. It was and remains fun to pick on the Heat now, easy to forget that LeBron picked them and then did nearly exactly what he did to the Cavs four years ago. There may not be a “Welcome Party” or a televised special, but we’re still enthralled with it. His website crashed on Thursday due to constant refreshes.

James misled Pat Riley and the Heat front office, as well as his supposed brothers Chris Bosh and Dwyane Wade, for a few weeks, trying to let his PR folks figure out how to handle it better this time around, knowing full well that most likely, the vast majority would be delighted he’d come to his senses and returned to Cleveland.

James misled Pat Riley and the Heat front office, as well as his supposed brothers Chris Bosh and Dwyane Wade, for a few weeks, trying to let his PR folks figure out how to handle it better this time around, knowing full well that most likely, the vast majority would be delighted he’d come to his senses and returned to Cleveland.

Should it – does it – matter that James did both the Cavs and Heat dirty, or can we even acknowledge this time around he did? See, we’re fine with certain things, a bending of the rules and the moral code, as long as we like the end result or the person.

We are fine with this decision because Cleveland needs him, he’s from there, Miami has more sunshine in a day that majority of us see in a week, Riley’s legendary status was not enough for once, the Heat had their success and you shouldn’t be able to win with your friends at a discount.

Above all, it’s just a heartwarming story. And man, are we a sucker for those.

You can be an egocentric individual and a great athlete – believe it or not, many before have. So LeBron James can be a great basketball player. He can want to be in Cleveland. He can be a good husband, a great role model and father, as well as tremendous at a number of other things. But can also be a disingenuous businessman.

It’s OK for us to admit these things, still want these athletes to succeed and win our favorite team’s championships. But we just can’t bring ourselves to admit anything like that.

We need them too badly.

We do the same thing with actors. We want to believe they are the characters we see in the movies. We’re stunned at the rumors and the arrests, disappointed they failed our expectations. And then we go right back to watching their films, because we need them way more than they need us.

We need heroes to distract us from our schedule-oriented, consumer-driven lives. We need them to wear the championship shirts, to have some seminal event to share half-drunk with friends, to bond with our children.

This is both understandable and remarkably sad at the same time.

We value the real heroes, the ones who died, sacrificed themselves for us and gave all to protect our freedoms. But we only do this on holidays where we are reminded of it. Our society, our culture, demands that our heroes forever be in our face, in our minds, lest we forget who we truly idolize.

We’ll always want and need Jeter, Jordan and James because they are someone to follow from a distance. And following at a distance allows us to not get hurt, to feign emotion and allows for easy backlash, if ever required. Our disappointment, while directed at them, is really with ourselves.

No wonder Twitter is such a big hit.

You may be asking yourself why this is a problem? Who cares and what does it matter?

Simple: our hero worship is so out of control that it is controlling us. We want our kids to be heroes, so we push them too hard, scream at their coaches and yell at their teachers. At the same time, ironically, we don’t want them embarrassed, so we shield them from possible pain and rejection. This is why everyone gets a trophy. This is why cuts are no longer publicly announced – even for a high school play.

In our own bitterness, resentment and disdain, we’re erasing the very things that balance us out and make us real for future generations: pain

Rejection and pain were meant to serve as a catalyst to something more. Once upon a time, they did. In fact, these very heroes we worship all have their stories of pushing beyond someone else’s no.

Now, we’re all too happy to use them as an excuse. This leads to a life of feeling sorry for ourselves, passing the days remaining in our lives by hoping for our hero’s successes or failures, all while buying their music, their movies, their jerseys.

Love or hate LeBron James or Derek Jeter over these past few weeks, we made them. We empowered them.

If we are even remotely interested in solving some of our bigger issues, it would serve us good to spend more time reflecting on what we can do to make ourselves less emotionally dependent on the success of others.

If we poured even 25-percent of what we give them into ourselves, I bet it would be amazing what could be accomplished, both as individuals and as a collective society.

The only problem is, those days seem long passed us now. We bypass challenges these days. We don’t pay even pay tribute in the right way.

We just throw lazy fastballs.

Right down the middle.