Thirty years ago this week, former Indiana University basketball coach Bob Knight threw a plastic red chair across the free-throw lane early in the first half of a 72-63 home loss to rival Purdue.

It was classic Knight, which is neither meant as a compliment, nor is it meant as a completely negative thing. It was just, well, another landmark Bob Knight moment during the height of the Bob Knight era.

The anniversary of this event provides an excuse to try to make sense now of the strange relationship between Knight, the school and the fans who loved him – and loved to hate him.

Bob Knight remains an enigma in the hearts and minds of fans of a certain age, even nearly 15 years after he last coached in Bloomington. It is one thing to watch a YouTube clip of a chair toss, or to read “A Season on the Brink” – but it is quite another to have lived through it.

And really, to understand Knight, to understand why fans still love him, but from a distance, you probably need to know that Bob Knight would never exist in this way today.

Oh sure, “The Chair” might happen, but Knight would have been suspended, fined or fired.

Maybe all three.

And probably within 24 hours.

Between social media and our viral news society, the entire world would have viewed the toss 10 million times by the following morning. Sports talk shows would discuss it, Knight, his mental state, who was to blame, what should be done and how it affected the players, officials and fans in a matter of three hours.

Better stated: If we make a big deal about touchdown celebrations, deflated footballs and the smallest hints of impropriety, what would we do with Knight in 2015?

In 1985, the Big Ten suspended Knight one game, and probably only did that because they had to do something. The media favored him, especially in Bloomington, and there’s little doubt that story did not make the regional or national news, at least not the way it would have today, with big, bold font and a catchy headline.

Yet there remains another reason that Bob Knight could not and would not exist in the same manner or fashion he did back then: The world – not just the game of basketball – has changed, evolved and grown. Knight has not.

Indiana (the state) in the 1970s and 1980s was dominated by basketball, in a way that must have been experienced, not told. Between the high school state-wide, single class tournament, Notre Dame, Purdue, Indiana State, Butler and Indiana, the state had a plethora of future pros and all-time legendary players come through.

The coaching characters were just as bold: Digger Phelps, Gene Keady and of course, Knight. Loud, intimidating, charismatic, bold figures cut from a cloth of execution and perfection. To be fair, there are times I wonder if many of the coaches from basketball and football would survive, even at their primes, 30 years into the future.

Perhaps the biggest factor of all: Indiana was less developed in the 1980s than it is now. This means lots of rural towns, connected by state highways and county roads. It means less to do in a city like Indianapolis, in towns like Fishers, Carmel, Greenwood, Brownsburg, Avon and Greenfield. It means there were only four TV stations – and cartoons aired on Saturday mornings.

It means a lot of free time to practice, play and watch basketball.

The house I spent my early years in sat on three acres on State Road 252, about 40 minutes from Bloomington, built by my grandfather in the late 1970s. In the area between the detached garage and the house, was a gravel driveway where my first basketball goal went up. In the middle of the backboard, my father painted the interlocking IU logo.

“You hit the corners of the ‘U’, and the ball will go in every time,” Dad told me. My parents were huge Indiana fans. My father had Knight’s salt-and-pepper hair, and at a young age, I wanted to play for them both.

I learned to dribble a basketball on gravel. Saturdays were spent at the Boys Club in short shorts, weekdays were spent out shooting at the logo until the utility light flickered and the shadows prevented my eyes from reading the bounce of the gravel. (I learned early on, dribbling on rocks in the dark brings about a bloody nose for a six-year-old.)

Evenings were spent watching the Hoosiers and Bobby Knight, a.k.a. the General. My memories of youth are interwoven with Martha the Mop lady, Don Fisher, Chuck Marlowe and John “Laz” Lazkowski and Indiana games on WTTV-4. In fact, to this day, I can do a dead-on Don Fisher impersonation.

The rest of my free time was spent pretending to be a player on a Nerf goal in our rec room. Mainly, it was always the National Championship game and I methodically recreated “The Shot” – Keith Smart’s baseline jumper to win the 1987 National Championship – every single time I played. Sometimes, I’d redo the sequence until mine went through the basket. I’d celebrate. I’d conduct my own TV interview. My dad, and thousands of other fathers, had the red sweater and golf shirt combo Knight nailed down, like a uniform of his own.

I tell all this because there is no conceivable way I was the only child of the 80s in Indiana who did these things. Some loved Purdue and the Boilermakers, like my parents’ best friends and their boys, others loved Notre Dame or Butler. I tell this as an example of why everyone loved and obsessed over basketball. And all the boys believed they would play for their school. Much of this had to do with the character of The General.

Reading the stories, the books, you were convinced that there was a method to Knight’s madness, which everything he did was to make you better, as a person, as a player. There are countless former players that swear by him, fewer, but still numerous that swear at him.

What “The Chair” should have shown us, had our eyes not been so blinded, our discipleship so strong, was that there was far less method and much more madness.

Bob Knight did not throw a chair across the floor because the officials were just that bad (Knight actually respected one of the officials, Phil Bova, deeply and later worked a clinic for him for no charge).

Knight did not throw a chair across the floor because his team was having a bad season by his standards (which was true, considering IU was a preseason top-5 team after an Elite 8 run in ’84 and upset of North Carolina).

And Knight certainly did not throw the chair to help out an elderly lady he said was asking for his seat, should he not be using it, as he told David Letterman in ’87.

No, Knight threw the chair because he could not stop himself from throwing the chair. Knight lacked control, probably always did. The method really got lost in his madness. And as time went by, that remained Bob Knight’s biggest obstacle. He couldn’t control himself and demanded from everyone else what he himself was incapable of – what all are incapable of: perfection.

Knight demanded maximum effort and precision. He demanded focus in the classroom. He demanded the most of his players, every day, all day. This makes him not at all different from thousands of other coaches.

What made him different was he simply could not tolerate when these things did not occur all the time, in the manner in which he wanted them. Someone who sought control was inevitably brought down by his own lack of it. It is one thing to strive for perfection, to push your players to reach for it, but it is quite another to deem them failures or to punish them emotionally, physically for the slightest mistakes.

There was no margin of error with Bob Knight, and his true method was in recent years as something he calls “The Power of Negative Thinking.” He has said that the worst word in the English language is hope. Perhaps that is because he lost hope in others before they ever did themselves. A self-fulfilling prophecy in many ways.

There is irony in the fact that Knight was the last to coach an undefeated college basketball team with Indiana in 1976. Perhaps obtaining that perfection changed him, hardened him in a search for duplication over the next 10-15 years. As Kentucky chases that immortal status this college basketball season, as UNLV nearly did in 1991 when they reached the Final Four before falling to Duke, it is known that chasing perfection is draining, demanding and most of all, unsustainable.

Perfection cannot be maintained because you begin losing it the moment you achieve it. In sports, someone will find a way to defeat you after long enough. Or you’ll just have an off day. But Knight dug his feet in a little more each year. Like any general, he would make everyone else change, but he’d stay the same.

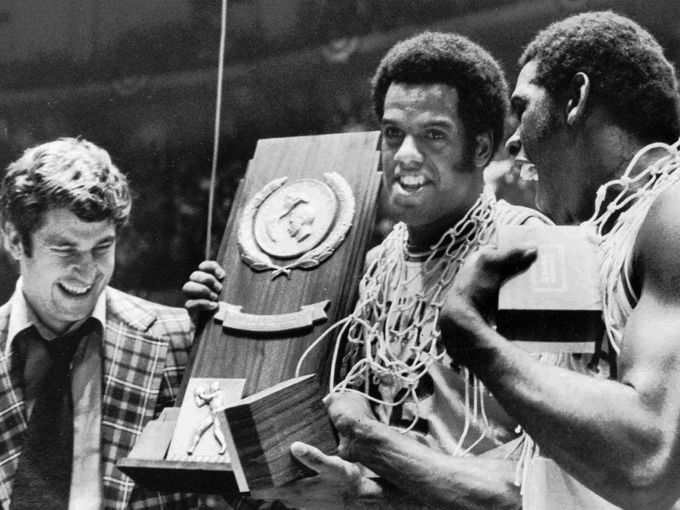

Truth be told, Knight did in fact change in the mid-1980s and into the 1990s. He stopped wearing suits, switching to golf shirts and polos before arriving at a pullover (the modern day equivalent of Bill Belichick and his hoodie). He seemed to grow colder to his players, at least publicly. He lost more players to transfer, had more players in his doghouse for longer periods of time. Look at the picture above, he smiled in 1976. He didn’t smile much in 1996. Some of his better teams in the 1989-1993 range had some of the strangest blowout losses and even with those loaded teams, never won another national title.

And this is when he lost me, and most likely when he lost many, many others.

As I reached high school, I was still playing basketball and still had that dream of Indiana (even though I knew I was not good enough to get there). But the more I watched Knight through the eyes of a 14-year-old, the more I saw that this didn’t seem like something I wanted for myself, even if I would have been able to have it.

The head-butts, the jokes about whipping his players, the feces covered toilet paper. I read “A Season on the Brink” around this time – and it absolutely terrified me looking at it through a player’s eyes. For some reason, when reading Knight’s quotes in the book, the voice in my head immediately sounded like R. Lee Emery in “Full Metal Jacket.”

What 18 to 22-year-old kid is equipped to step into the mind games a 50-year-old coaching legend is playing with them? Knight should win those games. And that dominance over others is certainly a component of Knight’s demeanor as well.

Meanwhile, I began watching other basketball teams and their coaches in the mid-1990s. Dean Smith seemed kind, yet passionate and disciplined. Knight’s former protégé, Mike Krzyzewski, had built Duke into a national power and his players seemed to love him, too. The same for Lute Olson, and his Arizona teams moved up and down the floor, not stuck in a stagnant, set motion offense. Olson’s players were always smiling, seemed to be having fun. Indiana players looked depressed and scared.

All of these men – except for Knight – have a court named after them, a sign of the lasting effect, the impact and the accomplishments. Knight has nothing left in Assembly Hall but the fading banners dated 1976, 1981 and 1987.

Though my skill level, height and ability did not match major Division I recruits, my mindset certainly did, meaning I wasn’t the only one who looked at Knight and knew that it would be a daily judgment and sentence handed down in Knight Court by Judge “General” Robert Montgomery Knight.

He couldn’t keep the best players in state and rarely got the better out-of-state players, either. Fewer and fewer star players wanted to play for him, which is what leads to not topping 23 wins in a season for his last seven seasons at IU and first round NCAA Tournament exits in five of the seven years. By the end of his tenure at Indiana, it was little surprise it ended the way it did. A crusty, curmudgeon bitter over a freshmen’s perceived lack of manners and a lingering tape of him choking Neil Reed, a non-descript player who seemed to give everything for Knight on the floor, but never could gain his approval.

The world changed, but Knight would not. Values, respect, seeking perfection and discipline will never go out of style. Demanding, demeaning, degrading, embarrassing? Those do go out of style, like a plaid jacket.

Which brings us back to present day, when Indiana fans awkwardly interact with the memories of Knight and his fantastic teams – the guts of the school’s illustrious basketball history and tradition. They talk about the tradition, the candy cane warm-ups, the floor design on Assembly Hall, the banners. They rarely mention Knight. It’s like trying to remember the presidency of Roosevelt, Eisenhower or Reagan without saying their names or conceding they were the President.

This is because there is no closure, even now, nearly 15 years after his departure. We embraced Knight for nearly 30 years in Indiana – even fans of other teams miss him – but we cannot bring ourselves to patch it all up without acknowledging our role in accepting and allowing it.

Truth be told, as wild and manic as Knight was, it is hard not to miss that era a bit now. I watch less college basketball than I ever have before. The games are not as exciting as they once were. Or perhaps I’m more distracted, or have more options to spend my time doing a litany of other things. The world developed and evolved. We kind of, you know, left the Indiana of the 1980s behind. Our little towns are small cities now, Indianapolis does anything but “nap.”

We left a lot of that time period behind in sports, too. Conference re-alignment changed so much of the landscape, as did the plethora of players leaving school after a year or two. Indiana went to multi-class basketball before Knight was fired (1998). Lots of other sports and activities are available, as is cable TV, technology and loads of other time distractions. The investment is not as deep as it once was. That is also neither good, nor bad. Just the way it is. Times change, but something about the fact that Knight never did is oddly comforting, yet disconcerting all the same.

Now, and perhaps finally, in a proper way, with enough time and distance to handle such things, we can begin to figure this all out. Indiana, the school and the state, has to determine how to admit that it loved Bobby Knight, while also yielding that his methods expired and that he was a megalomaniac.

They have to accept that his ego probably won’t ever allow him to step foot back in Assembly Hall, that the same ego is expecting a grand apology. You must understand that Knight does not believe – probably never believed – he did anything wrong. He once said he wanted to be buried upside down so the world could kiss his backside. If he does return while still alive, there will be some serious backside smooching that must occur by Indiana. Not because it is due or warranted to Knight, but because it is the only way he’ll come back. He just won’t change. Then again, maybe Indiana won’t change, either. And maybe they shouldn’t.

But if it ever happens, if Knight can come back and time can ease the pain of the anger gone awry, it can be both a celebration and a little sad.

If it ever happens, it will no doubt be clunky and awkward and strange.

Basically, it will be a little bit more like life. A little less than perfect, not entirely ideal, but still getting the job done.

A little bit like a chair, clumsily bouncing across a basketball court. It’s not supposed to be there, but it is there all the same.

And here, in Indiana, the crowd will ultimately cheer either way.